Storm Warriors: Monmouth Beach Chapter

United States Life-Saving Service — Remembering Heroes

In the mid-1800s along the US coastline — between Cape Cod and Cape Hatteras — there was a most terrible record of shipwrecks. Of this region, the New Jersey shore was notoriously the worst — known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

Back then a growing American population and demand for goods increased the need for shipping vessels, both American and European. Between 1880 and 1900, the coast off Monmouth Beach alone had 10 recorded shipwrecks. During those times transatlantic shipping was at a record high and all sorts of vessels traversed the waters off New Jersey. Sailors then navigated by the sun, stars, moon, and horizon. Thousands of passenger and commercial ships moved up and down the coast and naturally an alarming number of shipwrecks occurred.

A Beginning

In March 1849, Henry Wardell, descendant of the first settler of Monmouth Beach, deeded a lot on the beach (across from today’s Park Road) to the US government. An informal lifesaving society built a one-room beach structure, 24-by-16 feet.

According to US Representative William A. Newell, who wrote the law creating a lifesaving service in August 1848, there were more than 120 shipwrecks just along the NJ coast from 1846 to 1848. Congressman Newell, who represented the shore area from Sandy Hook to Little Egg Harbor, had witnessed a deadly shipwreck himself, shortly after his graduation from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1839.

During a storm that summer he had watched helplessly from the beach as the Count Teresto was wrecked and all hands aboard were lost. Seeing the dead bodies washed ashore the next day had a profound impact him. An accomplished man — physician, NJ governor, and friend of President Abraham Lincoln — Newell later became the superintendent of the US Life-Saving Association, NJ District.

An informal life-saving service was organized after the infamous wreck of the New Era off Asbury Park in November 1854; nearly 300 German immigrants drown in that nor’easter. In the ensuing years life-saving service crews, the men who patrolled the beaches day and night and in all weather, routinely risked their lives in grand maritime rescues.

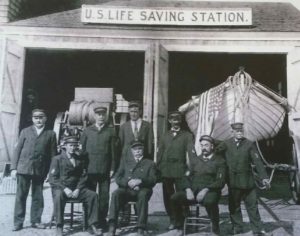

In 1871, the service was reorganized and the first station was built on Sandy Hook and then one every five miles down the coast. By 1878, the US Life Saving Service was officially formed. The state of New Jersey had the most stations (41).

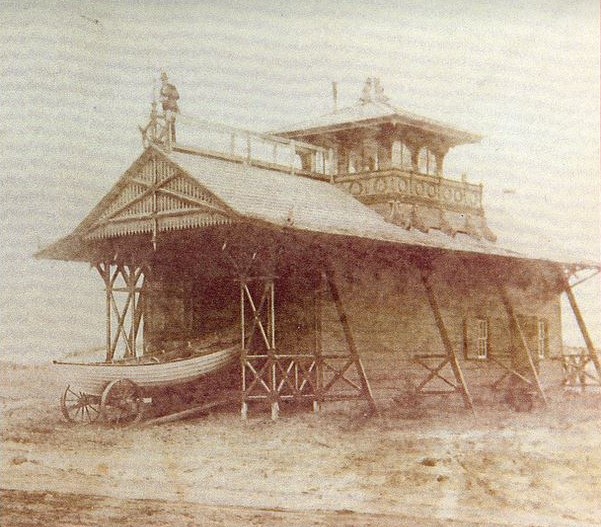

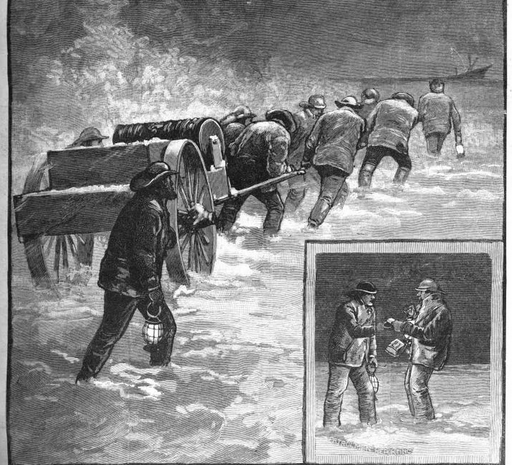

In 1880, a two-story Monmouth Beach station, known as #4 at Galilee (across from today’s Seacrest Road), was built. Six men worked the station and they were required to drill regularly, maintain the equipment, and patrol the beach at least three times a night. “Surfmen,” as they were known, would patrol until they met up with another surfman and exchanged brass tokens (called “checks”) as a verification. It wasn’t until late 1891 that the NJ stations could communicate with eachother by wire.

The life-saving service would be the first American governmental unit to adopt anything near “civil service” regulations. In 1882 a law was passed removing politics from hiring considerations and placing fitness for the job as the main qualification. By 1886, the federal government was in charge and agreed to man all the stations and pay the crews.

“You have to go out, but nothing says you have to come back.”

—US Life-Saving Service oath

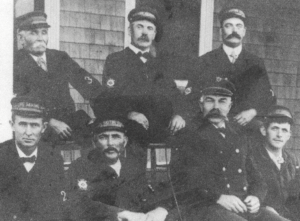

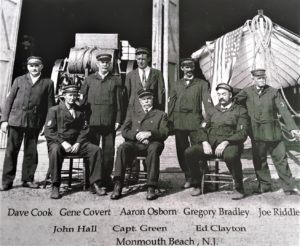

A life-saving service pioneer in Monmouth Beach was Major Edward Wardell, who served as Keeper from 1849 to 1875. Captain James H. Mulligan was Keeper of the Monmouth Beach station for over 20 years, serving from 1884 to 1905. In the beginning, Keepers were paid $700 per year and surfmen earned $40 per month.

Charles H. Valentine, Keeper from 1875 to 1884, led a team that earned the illustrious Gold Life-Saving Medal (the service’s highest honor for valor), for his “display of indomitable courage” during the single-day wreck of two ships, the E.C. Babcock (a 288-ton, three-masted schooner) and the Augustina (a 300-ton brig), off Monmouth Beach during a brutal February 1880 blizzard.

Surfmen Garrett White, Nelson Lockwood, Benjamin Potter, William Ferguson, and John Van Brunt were also awarded Gold Medals. In a hand-written note, US Treasury Secretary John Sherman (brother of famed Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman) recognized the acts and awarded the medals. The crew battled 85-mph winds, furious surf, and freezing cold. From that one single storm, surfmen from Sandy Hook to Takanassee Lake were called on to aid 5 shipwrecks over a 12 -hour period.

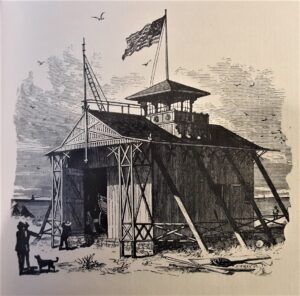

After damage from a brutal Spring 1894 storm, life-saving operations were moved to the west side of Ocean Avenue and a Duluth-style station designed by George Tolman was constructed. Wealthy industrialists George Fisher Baker and Edward Walton donated the land. The original structure has undergone several restorations and still stands today, as the Monmouth Beach Cultural Center.

Surfmen Bravery

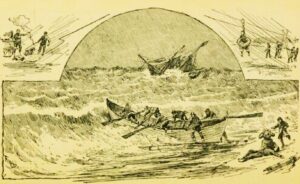

Revered as heroes of the Atlantic Coast, the surfmen’s pledge was “you have to go out, but nothing says you have to come back.” Using equipment like the beach-apparatus cart, lifeboat, Lyle Gun and breeches buoy, life-saving crews risked their lives in dangerous maritime rescues.

Their work was remembered in story and song back then, but today’s society has largely forgotten about the great sacrifice and dedication of these men who risked all to save others. Their true measure of heroic performance is amazing — from 1871 to 1914, the US Life-Saving Service aided 28,121 vessels, rescued or aided 178,741 persons, and lost only 1,455 casualties. That’s real “life-saving.”

In later years, after the invention of the Marconi wireless telegraph and more reliable steamships, wrecks were less common. Still, for 60 years, shipwrecks and the US Life Saving Station shaped the history of the state’s coastline.

US Coast Guard in Monmouth Beach — HERE

Super Saver — Major Edward Wardell was the US Life-Saving Service Keeper at Monmouth Beach from 1849 to 1875. Born in Monmouth Beach (when it was called “Fresh Pond”) in 1826, he died in March 1912.

US Life-Saving Station #4 at Monmouth Beach, NJ. October 1894. Pencil sketch by Milton James Burns (1853-1933).

An interesting story from the Daily Press on the status of the US Life-Saving Service in our area, August 1896

US Life-Saving Service Heritage Association — MORE INFO