A Once Fabulous Hotel

… the Epicenter of Monmouth Beach

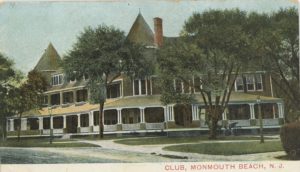

As a once sparse shore area known as “Monmouth Beach” was becoming a privileged resort back in late-1800s, at the center of the action was the spectacular Monmouth Beach Clubhouse Hotel. The fabulous imagery of this now gone facility is one of the hallmarks of Monmouth Beach.

Situated in the area around Beach Road, River Avenue and Club Circle, the massive structure included parts from the original late-1700s farmhouse built by the Wardell family, who first settled the area in the1660s.

The exclusive seashore spot — offering cool breezes, warm beaches, and elegant living — was all the rage in its glory days. According to Monmouth Beach: A Bicentennial Publication, the facility “reigned as a social and cultural center of the area for many years.” Matthew Houghton bought the clubhouse operations for $15,000 in 1872 and ran it for a quarter century, hosting at least two US presidents (Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley), the son of another (Robert Lincoln) and a vice president (Garret Hobart). US House Speaker Thomas Reed of Maine, a political powerhouse in the 1890s, was also a guest on several occasions. The son of a Massachusetts farmer, Houghton died in Sept.ember 1907.

For much of the late 1800s, the New York Times society pages were full of names of the wealthy and welt-connected who stayed at the hotel during the shore’s summer season. The railroad and a nearby train station was the feeder for the “select hotel.” The Red Bank Register called it “one of the most popular hotels on the Jersey coast” in its day when it could accommodate up to 200 guests.Many of the nation’s top theatrical and musical talents performed there and the casino’s roller-skating rink was a “craze.”

By 1890, the original developers had disposed of their holdings. Several wealthy New Yorkers put up $200,000 and the old resort hotel and surrounding properties were incorporated into the Monmouth Beach Country Club. The clubhouse hotel — re-designed by Romeyn & Stiver and build by C.N. Wilson at a cost of $40,000 — opened in 1891. The property also included several large neighboring houses (estates really) available for seasonal rental, gardens, horse stables, and tennis and croquet courts. Future borough mayor, A.O. Johnson, was a clubhouse night watchman.

“True hospitality consists of giving the best of yourself to your guests.”

—Eleanor Roosevelt

In the 1890s, Colonel William Barbour, one of the late 19th century’s wealthiest men, was an active and connected clubhouse president. His large seashore mansion on Ocean Avenue was designed by world-renowned architect Stanford White (where the Admiralty now stands). It was torn down in 1973. According to a Long Branch Daily Record account, Barbour was known for entertaining “some of the first people of the land” and for conducting “the finest musical concerts of the Jersey Coast.”

Born in 1855, he founded and owned the Barbour Linen Thread Company, which manufactured linen treads for fishing liens and nets (a big business then). Treasurer of Republican National Committee when he died in March 1917, Barbour left an estate of $15 million. His pallbearers included then NYC Mayor John Purroy Mitchel and Charles Evans Hughes, a U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice and 1916 Republican nominee for President. Barbour’s son, William, was born in Monmouth Beach in July 1888 and represented New Jersey in the US Senate from 1931 to 1943. He also served as Rumson’s mayor.

MB Clubhouse Hotel Images — HERE

Even with wealthy patrons thorough the years, the resort had financial difficulties and several operators over the years. Shortly after the borough officially incorporated in March 1906, the clubhouse was sold at sheriff’s auction. In 1908, it was purchased by a syndicate led by Lewis Berg with plans to remodel and expand. In 1909, the club was leased by Thomas Hamilton.

Leonard Padula was the owner/manager in the early 1900s, when a flyer promoted the “Monmouth Beach Inn” as “Jersey’s most fashionable resort.” The pitch was that “the building is more like a manor than a hotel” and “nearly every room has a private bath with modern sanitary plumbing.” Facility guests had the use of the nearby bathing pavilion (now the MB Bath & Tennis Club), horse stables and a laundry on Willow Avenue, a golf course at Shorelands, and onsite tennis courts. There were also Special Sunday Morning concerts and a hunting lodge on River Avenue. All of the rooms came with an outside view.

To stay at the clubhouse hotel, under the European Plan, rooms ranged from $2 to $4 per day ($5 for an attached bathroom) and $12 to $30 per week. Under the American Plan, it was $20 to $30 per week for a single person and $40 to $50 per week for a couple. The cost was $5 more for an attached bathroom. The Inn’s culinary specialties were seafood, roast chicken and planked steak and the chefs and waiters were selected from the leading hotels in New York City. Breakfast (with 5 courses) was 50 cents, Luncheon (with 7 courses) was 75 cents, Dinner (with 10 courses) was $1.25 and Shore Dinner (with 15 courses) was $2.

A town native and longtime leader, William L. Blizard was the hotel manager for some 30 years until his death in April 1929. He also served as president of the borough council and school board and fire company chief.

By 1910, manager George Avery had made improvements including steam laundry service and an electric elevator. In 1915, a Canadian resident, Anita Duchastel, owned the property. From 1927 to 1929, the inn was leased by Major A.S. Stanford of Philadelphia.

In April 1919, Bernard Winfield and the Strand Corporation of New York acquired the properties (including inn and pool) paying $30,000. The Austrian-born Winfield would own the hotel until it burned down a decade later. He died in June 1964 at age 82.

The day after Christmas 1929, the facility was mostly burned during a spectacular fire. Hotel carpenter Charles Archer had inspected the building just a couple hours before the fire and reported no problems. By the time firemen arrived roaring flames were coming from the northeast corner of the building near the trunk elevator. Despite the assistance of seven local fire companies, poor water pressure and gusty shore winds made the firefighting efforts very difficult.

According to an Asbury Park Press account, the only parts of the hotel to survive were “eight gaunt chimneys” and the West Wing, Bird Cage, and Park cottages. At the time of the fire, the hotel included 90 guest rooms. Owner Winfield had valued the building at $150,000; but insured it for only $40,000. Among his other regrets was “the loss of fine woodwork in the foyer.”

In the following years, the remaining portions of the old hotel were sectioned off and/or moved and made into smaller private homes. Only a few sections remain standing today.